Kayla Quan Challenges the Model Minority Stereotype Through Sincerity and Humor

Drea DiCarlo talks to San Francisco-based Kayla Quan about the complexities of race and

ethnicity in her lighthearted and facetious illustrations, prints, and zines.

Kayla Quan is a Filipino and Chinese third-generation American artist based in San

Francisco, CA. Her work takes the form of prints, drawings, collage, and text-based images,

and uses ironic humor to comment on people and situations in her life. Often adopting an

informal DIY aesthetic, her work is very personal, like a look into one’s diary. She uses her

art as a means of coping and emotional expression. The vulnerability in her work invites her

viewers to validate their own feelings. Quan also uses her work to explore issues of race and

the Asian American experience of being exotified and othered. Her drawings and prints make

heartfelt statements on navigating loss, identity, and coming of age.

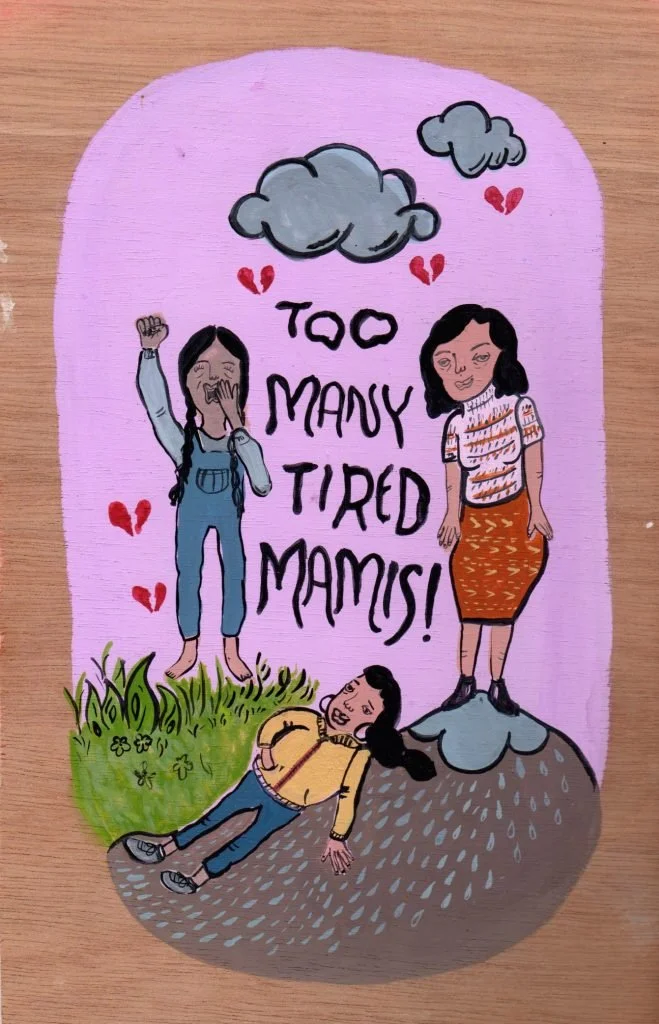

Too Many Tired Mamis by Kayla Quan. Image Courtesy of the Artist

DREA DICARLO: Your sketchbook drawings use little poetic phrases that are playfully

naïve, ironic, and assertive, used as a means of articulating difficult thoughts and

feelings. As a collection, these sketches convey a sense of sincere hurt or

melancholy. What is the role of text and language in your work?

KAYLA QUAN: I’d prefer to view my work as wry or tongue in cheek. I think discerning the

vocabulary used to describe my work changes the tone of how viewers perceive it. With that

being said, language and text play a large role in my work. Most of my ideas for pieces stem

from words that I’ve jotted down, are strewn together, and eventually they take visual form. I

keep ongoing lists in my phone’s note section of short phrases, often reflective of passing

thoughts or pangs of emotion. My work is reflective of my current emotional/mental/physical

state of being; it’s often a platform for me to unload or express something that I feel

necessary to convey as means of coping. I strive to make things that are relatable, yet in a

way that feels real and vulnerable, while simultaneously making fun of myself.

DD: What is the process of choosing phrases and other texts? What is your

relationship with writing as a visual artist?

KQ: Much of my work is developed during bouts of sadness, not because I wish to exude an

overall depressive mood, but simply because it’s my way of expelling negative thoughts. It’s

my way of saying, “hey, sometimes I’m sad (or lonely, longing, nostalgic, hurt, etc.) and I bet

all of you are too, and that’s totally ok and human.” Sincerity is important to me in everything

that I do. I’ve never really thought myself to be really good at anything besides being

sincerely genuine in my interactions with humans. My work conveys a sense of melancholy

because I let myself be raw with my words and thoughts to interrupt those feelings. My

overall mentality is to let it all hang out, and let others relate or connect to it in ways that

hopefully combat sincere hurt.

As far as my process for choosing phrases and text goes, there is no real formula. Like I

mentioned earlier, I keep a back stock of words on my phone and sometimes I’ll refer back to

the list and I’m prompted to make something visually from them or vice versa. I’ll see visual

inspiration somewhere and then will create something that just so happens to synchronize

with a phrase I wrote months before. The text I use are often short in length, primarily

because writing lofty pieces makes me feel out of my element and honestly, pretty cheesy. It

isn’t that I don’t care about what I’m saying; I do and that’s why I reject the notion of being

flippant. I’d like to see my work as being the opposite of apathetic or disrespectfully avoidant

because I’m being open with my feelings and earnest in the only way I know how to be. I like

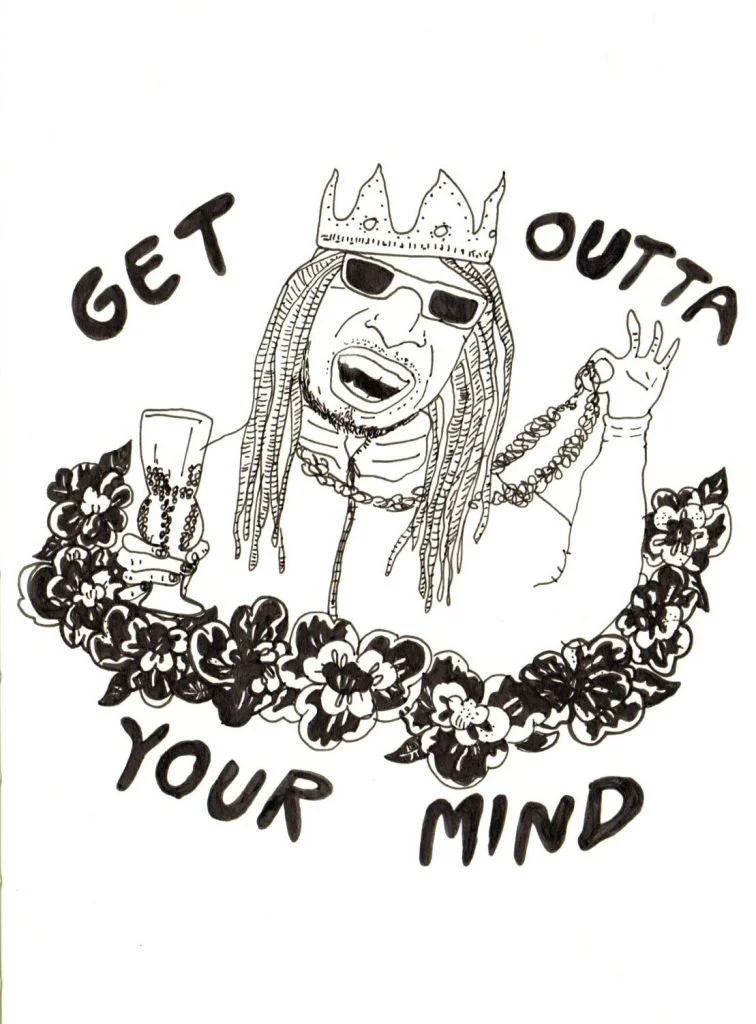

to make things that are humorous, yet telling and relatable on a real level, for example this

drawing of Lil Jon (please read caption & comments).

Lil Jon Sketch by Kayla Quan. Image Courtesy of the Artist

DD: Visually you experiment with various modes of mark making and transferring of

images through printing processes and drawing that acknowledge the presence of the

hand. What is important about the presence of the hand in your work? What is

important about the presence of the hand in your work? What is the relationship

between altering photographic images and your drawings and illustrations?

KQ: I’ve developed a style that is distinctive and imperfect, but true to myself. For a long time

I made all of my illustrations in one go, just pen to the paper and no pre-plans. Drawing this

way made me develop a greater sense of artist intuition by allowing myself to work off of

happy mistakes. I guess that’s kind of how I see all of my art: it’s all a bunch of happy

mistakes that somehow work in my favor. Not until recently did I start drawing with pencil

first. I’m constantly developing as an artist, but I do feel like I have a concrete style that I

don’t ever steer far away from.

Adding my hand in old family photos give the photographs new life in the context of my

current life. Pictures speak for themselves, but I wanted to do a little extra by telling my

family narrative from my perspective. Adding text and illustrations on top of these photos let

viewers know that my hands worked with the photos—it’s like leaving visual traces of my

essence on snapshots of distant pastimes. Like most of the things I make, this illustration

and photo process is just my way of making sense of my world. And by sharing my work with

others, it’s my way of welcoming people into my brain. It’s your ticket into seeing things from

my perspective.

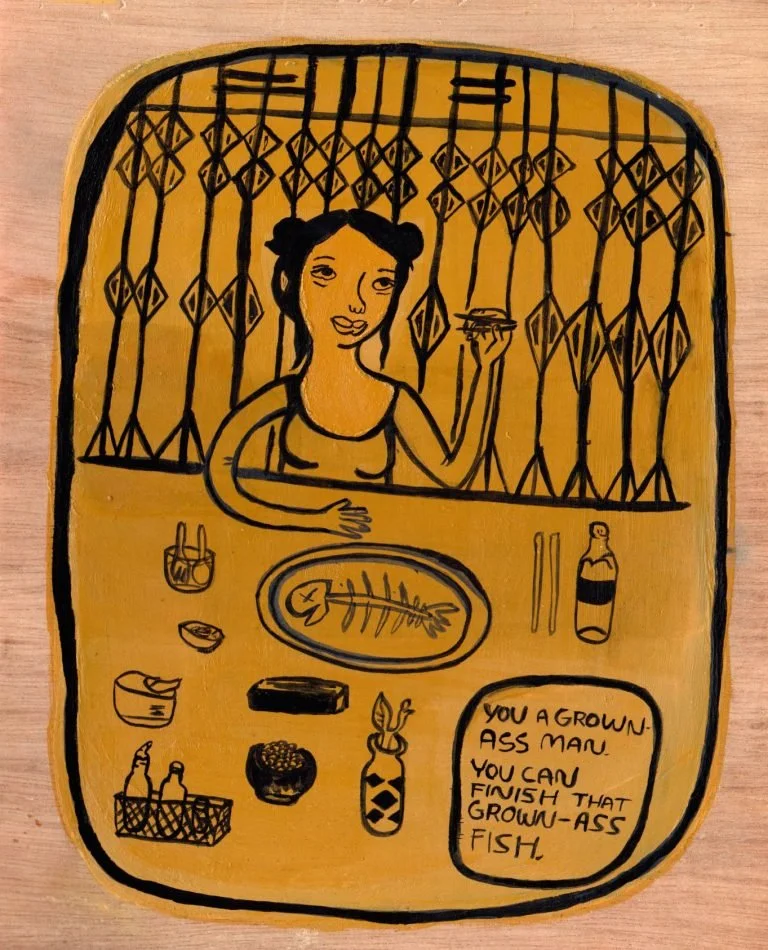

So I Creep by Kayla Quan. Image Courtesy if the Artist

DD: In your work, you alter photographic images, recontextualizing nostalgic

memories with energized interventions from the present. Similarly, handwriting

visually and conceptually interjects each work, welcoming the viewer into a subjective

space of introspection. Through your distinct making process, how do you hope the

work connects with viewers?

KQ: A handful of people have actually asked me about the meaning behind my print So I

Creep~Ya (2014) because they all thought that “creep” was directed toward my dad. The

original photo is a Polaroid of my dad, my sibling, and myself wearing my dad’s Ben Davis

work shirts. I used to always smile in that funny square-mouthed grin like a lil’ creep. I

doodled a bunch of faces in the background to represent visual personifications of my active

imagination as a child and presently as a young artist.

DD: In your zine What the Fuck Kind of Human (2015) there is an excerpt that ends

“I’m my own person, not defined by race.” This yearning to be recognized beyond the

construct of race, seems in contrast to the phrase you use in another work “Yellow

Voices must be heard,” which emphasizes the drive to center and organize around

Asian American voices. Can you expand on the complexities of race and identity for

yourself as an artist? How do you reconcile this conflict and in what ways do you see

these working together?

KQ: So by definition, “community” entails inclusivity and a means of constructing identity as a

result of sharing common characteristics or interests. However, “community,” also implies

exclusivity as much as it does inclusivity. Race is often a place where people align

themselves in a community. Race is visual characteristic. For me, it’s often the first thing

strangers ask me questions about: “What are you?”—always a dreaded question—“Where

are you from? What’s your racial background?.” Race is and can be a defining characteristic,

but I don’t want to be pigeonholed into racial stereotypes—which are more often than not

untrue, hurtful, exotifying, essentializing, tokenizing, and demeaning.

That excerpt, where my friend says “I’m my own person, not defined by race,” is a true

feeling of being fed up with people making assumptions about your personhood based

around the confines of “Asian” stereotypes. This statement is a response to being

multifaceted, but never being fully recognized as anything more than just “an Asian girl.” It

sucks when people place perimeters around who you are or should be.

I thought a lot about using this term, “Yellow voices must be heard.” Using “Yellow” in

regards to race is often deemed derogatory. However, as a person who identifies as being

Asian American I feel it fair and in my right to reclaim this word. For me, it was an

appropriate unifying term that seemed the most inclusive to me. It’s a response to looking

Asian but also feeling excluded from not being brown enough and not being white either. It’s

my way of place making for my skin color and my identity as a Chinese and Filipino

American female. “Yellow Voices:” it’s a contentious phrase that I’m willing to debate; for me,

it’s a rallying cry intended for my community and not to be misused by others.

Race is a social construct that I’m constantly trying to unpack and deconstruct in terms that

feel good for my own personal growth. I spent my early childhood in the Bay Area where a

large majority of my classmates were Chinese or Filipino. I felt proud to rep my roots. Then, I

moved to Orange County from middle school to high school, and this is where I first became

aware of my race in a negative way. I’d never had people yell racial slurs directly at me

before. I’d never had people laugh at me just for being Asian. I grew up in Orange County

being the “skater Asian girl” or the “cool Asian;” I was never described without my Asian

identity yet I don’t even speak any other language besides English. I was born in the United

States and so was my father, and so was my father’s father. I had never even been to the

Philippines or China until this year. So, why must I constantly be othered strictly off the basis

of what I look like?

For a long time, I grew up in the suburbs where I felt like being Asian was an embarrassing

quality, and that “White” was what I was supposed to strive to be like. Art has become an

outlet and a platform for me to ask these big questions and grapple with the complexities of

race with others. It feels good to make things and to be comforted by other people’s

narratives.

Siem Reap by Kayla Quan. Image Courtesy of the Artist

DD: Your woodcut Silence is Violence (2015) follows a tradition of activist art that

includes the visual artwork of Emory Douglas, the Minister of Culture for the Black

Panther Party, and 1960s United Farm Workers of America. In contrast to protest

artwork of the 1960s and ‘70s, the girl and woman coded figures depicted in Silence is

Violence are passive in their postures and gaze; they do not confront the viewer

directly. What were your intentions behind this imagery? Do you believe that you are

enacting a type of “soft” resistance, a type of resistance where individual Asian

Americans defy the model minority stereotype? How does the phrase “Silence is

Violence” particularly apply to the Asian American community? How do you see your

role as an artist within this narrative of activism and resistance?

KQ: The “Silence is Violence” woodcut was born out of a poster assignment. I immediately

took to alluding to traditional activist art and studied poster artwork from the 60’s and 70’s—

propaganda, UFW, [and] anti-war (during the Vietnam War) posters of that era. The 3 figures

depicted in [this work] convey the transformation from inaction to action, from passive silence

to engaged presence. For me, the process of personal transformation from dismissive or

timid of conflict, to being willingly vocal and demanding of my needs is, and has been, a slow

but organic process. In total, my work takes on a “soft” quality to it because my overall

demeanor as a person isn’t one that is outwardly aggressive.

Activism doesn’t have one distinctive look. Activism can look a lot of different ways, and the

way one chooses to protest can reflect a lot about their cultural self. There is no linear path

toward healing.

“Silence is Violence” is typically a slogan used in anti-rape and sexual violence activism, but I

felt it applies specifically to Asian American communities because there’s an overwhelming

trend of silencing our struggles and pain to appear as “model minority” citizens. In cultures

that pride respect and honor, adversity is something that must be handled quietly and swiftly.

Silencing someone’s pain and not discussing personal or community struggles is violent. I

can say that I come from generations of familial dynamics that do not encourage transparent

communication about personal issues. My parents are well-intentioned people, but I grew

being told not to be so sensitive all the time; my sensitivity was seen as a sign of weakness.

I know a lot of my Asian American friends have either a hard time or zero experience with

discussing personal mental health with their families as well. A lot of people think that model

minority stereotype is a compliment, but it’s actually harmful to pan-Asian communities due

to its silencing properties. Overall, I think my community benefits from hearing messages that

encourage [one] to speak honestly and to be politically active. I think art and activism are

important. Art is an effective vehicle for making your message accessible and visual to broad

audiences.

As far as how I view my role as an artist of activism and resistance goes, I’d say it’s just

something that is. I start projects based out of necessity for myself, and then secondly for

what I think could benefit others to see, hear and share. I get really excited when I see other

artists, educators, or activists that look like me or have similar cultural experiences.. I also

find a lot of joy in receiving comments from fellow Asian Americans that are stoked about my

work, or when they express that it’s relatable or needed in our communities.

This interview was edited and commissioned by the 2016-2017 Charlotte Street Curator in

Residence, Lynnette Miranda, in collaboration with Informality‘s for Issue 2: Digital Studio

Visits and the exhibition ¿Qué Pasa USA? at la Esquina Gallery (1000 West 25 Street

KCMO) open from November 18, 2016 through January 7, 2017. This interview was

originally published on http://collectivegap.info/