Dominique Carella Questions Identity Constructs By Reclaiming Language

That Awkward Moment When by Dominique Carella

Camile Messerley talks to Dominique Carella about pointing to the absurd social

constructions of gender, race, and ethnicity by reclaiming language in her text-based

installations.

Dominique Carella is a recent graduate of the University of California, Santa Cruz, where she

received her Bachelor’s degree in Sociology and Visual Arts. For the exhibition ¿Qué Pasa,

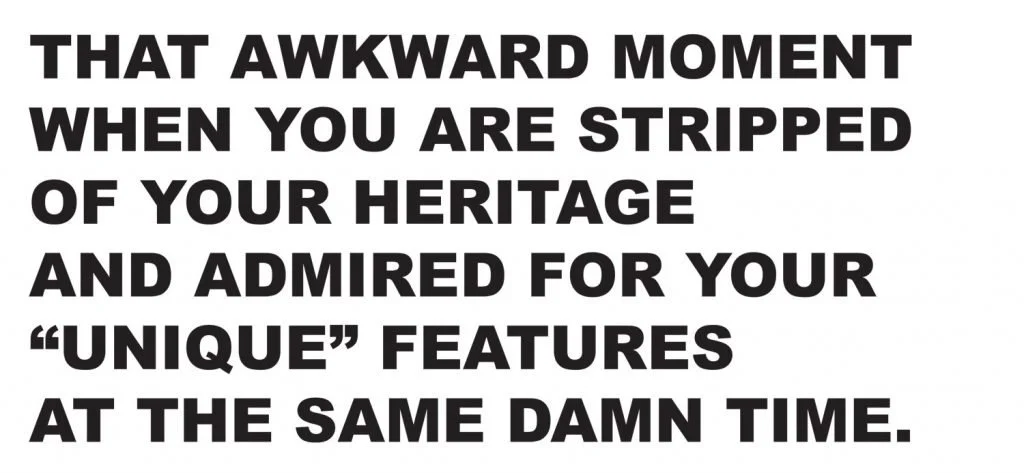

USA?, Carella, created a large scale vinyl text piece entitled That Awkward Moment When…

(2016), which is accompanied by a postcard sized take-away, I am Only Boricua When

(2016). She analyzes the societal structures of race, gender, and ethnicity primarily through

the use of language and text as medium. In this she is also calling awareness and attention

to the microaggressions and oppressive language Women of Color experience everyday.

The exploration of these ideas comes first from personal experience growing up in San

Francisco, and uses this environment which she has lived in since childhood in her practice.

Carella’s practice has been impacted by graffiti, urban slang, and pop culture as a whole.

Due to these influences, her work ranges from the sharing of very personal accounts, to

looking at institutionalized forms of oppression through visually stimulating large scale

installations.

As Carella continues to work with text in a variance of mediums, the progression and

extrapolation of her subject matter and the issues she faces and works with will be key in the

political state of the country post-election. To quote Carella “my work is very much a

reflection of my daily interaction with the world around me, and I know I’m going to have a lot

to say in the next four years.” Being that as it may, I look forward to the calls from Carella that

hold the capacity to further community engagement and interaction of not only in her home

base that is the bay area, Being that language can be shared at the speed of Google Fiber,

this work has the ability to travel as is it did to ¿Qué Pasa, USA? in Kansas City, Missouri.

CAMILE MESSERLEY: Your work in ¿Qué Pasa, USA? is all text driven, pulled from a

personal response, feeling, or reaction to oppressive language directed at people of

color, more specifically women of color. These works follow ridiculous and

hyperbolized social constructions for race, gender, and ethnicity. Can you expand on

your use of language as a medium, and further your use of language as a critique of

these oppressions?

DOMINIQUE CARELLA: Often, I will produce dozens of ideas or phrases and only end up

using one. The phrases that I choose come to me very naturally, I believe the more I over

think, and edit and rearrange a single phrase, the less organic it seems, so I usually stick

with the first wording that comes to mind.

My process begins with my inspiration, with an encounter, a conversation, a music video, a

magazine headline, really anything that pisses me off. I then take my experience and put

them into words that the public can understand, often through humor, or pop culture

references. Like I said, my process is very organic, the more I over think my work the less

effective it is. I take my anger and turn it into something that will start a conversation, I add a

little humor so that people can digest it, but I also make sure that it has that raw and honest

element masked beneath the humor that starts the conversation.

CM: Can you talk about your editing process? How are grammar and syntax part of

your practice?

DC: Editing comes into my practice by a process of elimination, I may start with dozens of

phrases, but it comes down to picking the phrase that is the most thought-provoking, the

most eye-catching, the most likely to ruffle some feathers and to start a discussion. [it] is also

dependent on the space I will be presenting the piece in and who the audience is. Textbased

pieces can draw a lot of attention, so it is important that it works with the space—

some pieces work better in some environments than others, that is just the nature of the

work.

Grammar is incredibly important to me in my work. A lot of my work stems from my

experiences as a woman of mixed heritage, I am pretty much 100% of the time perceived as

a completely white woman. I am a first generation college student, and to me, my education

is one of the most empowering things I possess. I believe that I am taken more seriously

because I am perceived as a white woman—my successes are never questioned because of

my whiteness. I believe it is crucial for my practice, that my knowledge, and my successes as

a woman of mixed heritage become apparent through my use of grammar. I love pairing

proper grammar with pop culture references for example that hint towards my age, my

ethnicity, and my experiences as a woman of mixed heritage.

50 Simple Things Americans Can Do To Save The Planet by Dominique Carella

CM: What is the relationship between That Awkward Moment When… (2016), the large

text installed in vinyl letters, to I am Only Boricua When (2016), the postcard sized

take-away texts that were below the wall piece. How did you conceptualize and decide

in terms of the physical manifestation of the work? Furthermore, what do you think

about the relationship between accessibility and scale in your work?

DC: To me, the bigger the better. Whenever I do a show I like to know what kind of space I

am working with. My work is very adaptable, it can be large, it can be small, it can fit in many

different kinds of spaces, but if it were up to me I would have my pieces take up entire walls.

I like the size of my shorter text pieces to be dramatic and overwhelming. I often produce my

shorter pieces with stencils and spray paint, but for this show the vinyl was crucial in creating

a clean aesthetic that worked really well with the take home postcards.

The scale of my work is really crucial in understanding where my work stems from. My

shorter text pieces, like the large vinyl piece on the wall, are often less vulnerable, they stem

from moments of anger, and they are appreciated by the masses even if it does piss a lot of

people off. The larger works really illustrate my anger or frustration, literally [through] the size

of the work. In comparison to my take away piece, my longer in depth writing is much more

vulnerable, it stems from very personal experiences and moments of sadness, grief, change,

and strength. I feel like the personal element of the writing works very well with the takehome

notion of the work; you can take the piece home, read it, love it, hate it, resonate with

it, whatever it may be, but the second I put the text on a wall super large for the public to

digest, it changes the piece.

CM: In terms of the next step, where do you see yourself in this work and where it

might be going? How do you plan to further this concept? What are you working on in

your studio currently?

DC: My work has changed pretty drastically in the last year, I went from producing pretty

large-scale site-specific installations, to text-based works that come from my personal

experiences, as opposed to addressing much larger societal issues. I believe my work will

become more vulnerable the more I produce, and eventually I will have a collection of longer

text pieces that address a variety of personal experiences. I definitely plan to continue with

this concept, there is a lot to work with when your practice stems from your personal

experiences and digs deep into your relationship with the world around you, especially in this

moment in time.

Right now I am working on developing more text pieces, and producing them on different

mediums, and experimenting with different sizes and how that changes the piece. In

between larger projects, I love putting my work on stickers and other mediums that stem

from street art and graffiti. I write a lot in black books as well, and am currently exploring new

ways to include my black book work into my contemporary art practice.

CM: I saw that you’re a recent graduate, do you have any thoughts or hopes and

dreams for the near future? How has the election affected your practice and what you

are currently working on?

DC: For many, many, days following the election I was definitely in shock and very

depressed, that was the general consensus in the communities I occupy, alongside anger,

and the desire to create change. The election will definitely affect my work—my work is very

much a reflection of my daily interaction with the world around me, and I know I’m going to

have a lot to say in the next four years.

This interview was edited and commissioned by the 2016-2017 Charlotte Street Curator in

Residence, Lynnette Miranda, in collaboration with Informality‘s for Issue 2: Digital Studio

Visits and the exhibition ¿Qué Pasa USA? at la Esquina Gallery (1000 West 25 Street

KCMO) open from November 18, 2016 through January 7, 2017. This interview was

originally published on http://collectivegap.info/